|

| "Reflections", photo by J.J. |

Whether you are sketching a real landscape or marking things of interest in a photograph to make a pattern you can follow in your needlework, limit yourself to 45 minutes. Set a timer or arrange for a reminder on your cell phone. This will force you to simplify what you include on your pattern, leaving out unnecessary details. Try to capture the essence of the place you have chosen for your subject. You might want to follow J.J.’s suggestion and half-close your eyes so you aren’t seeing minor details and can become more aware of major forms and the spaces between them. You will also become more aware of the masses of light and dark when you are not distracted by unnecessary detail. What you leave out can be just as important as what you put in. You will want some repetition of shapes, lines, and colors in your picture to both “pull it together” (unify it) and to give it variety so that it doesn’t become boring. Be careful that you don’t repeat any of these things too often.

|

| Sketches of the same tree in four seasons |

One of my favorite landscape painters, Zoltan Szabo, put it this way: “The human mind tends to organize everything to death.” For example, when a person plants trees, they tend to be the same kind of tree, arranged in straight lines, equidistant from each other and meant to grow to about the same height. When Nature plants trees, they are in interesting clusters of different species and different heights, colors, and textures. Believe me, Nature is by far the better artist! From my kitchen door, I can see three kinds of evergreens and about a dozen deciduous shade and fruit trees. I can observe them and study them in all four seasons. I can mentally move them around into any combination I wish. Find a place with good trees and get to know them, capture them on paper or film, and keep them for reference.

|

| A winter scene by J.D. |

Trees are important components in many landscapes. Here’s an assignment for you. Get a library book or use the search engine on your computer to look up works by the Impressionists. Study the way they painted trees. Compare them. Be sure you include work by Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Signac, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley. If you can find them, look at the work of Dominique Lang (Luxembourg) and Friedrich Eckenfelder (Switzerland). Choose one or two examples of the artist’s brushwork and try to think of stitches that would give you similar textures and effects. Try some of them on scraps of fabric and file the ones you like.

|

| "Heading Over the Hill", photo by J.J. |

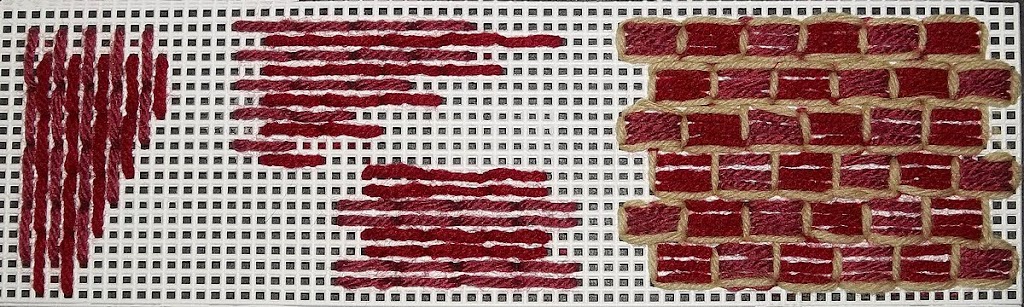

If you are using something like a fence, wall, or stream to lead the viewer’s eye into your picture, it should slant or curve into the picture. Ideally, it should disappear once it has led the viewer to an important point, although it may appear again somewhere else in the picture. Remember that as objects stretch further away from you, they become smaller and less distinct, less detailed, and lighter and grayer in color.

Gray is a color you can use to get wonderful effects. Collect gray yarns or flosses. Use black sparingly. Like straight lines, true black does not appear often in nature. The posts and rails get lighter, thinner, and shorter as they recede into the distance. Here is a simple sketch that illustrates what I mean. If I were doing this in needlework, I would start the first post with 4 to 6 strands of dark yarn or floss and exchange one thread for a lighter one on the second post, two on the second, three on the third, and so on. See my discussions of blended yarn part II of this series (April 8, 2018).

|

| Pencil sketch of a fence |

|

| Transparent grid tool |

Speaking of points of interest, here is a simple device you can make to locate them. Start with a piece of thin, clear plastic and a permanent marker. Measure carefully. Put in two straight horizontal lines that divide your plastic into three equal sections. Then put in two straight vertical lines that do the same thing. The four places where the lines intersect are the attention (esthetic) points. These are the areas a viewer is likely to seek out first. Place the plastic on your canvas and mark the four points. If you are working on fabric, you may want to put in rows of long running stitches where the lines would be, Use a bright color that is not in the picture so that you can easily remove the lines when they are no longer needed. Choose one of the attention points for the area of greatest interest in your picture. If you have a second area of interest, it is probably best to place it at or near the attention point directly or diagonally across from the first one you chose. If you use the one directly above or below the first one you have shifted the “weight” of the picture to one side without anything to balance it.

|

| "Mountain Poppies" by J.J. |

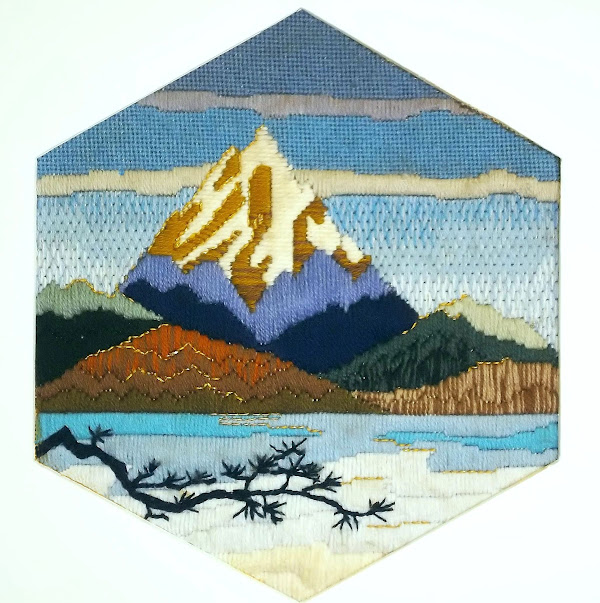

The three divisions on the plastic device represent the three planes of the picture: foreground, midground (or middleground), and background. These are the aspects of perspective that make a picture look three-dimensional on a two-dimensional surface. In a landscape, you need to pay attention to the distance that appears to exist between the viewer’s eye and the furthest object in the background. If the proportions do not look correct, the scene will not be believable. This does not mean that the three planes always have to be of equal space or have equal emphasis. Ordinarily, the focus would be on the foreground because it is the closest to the viewer. Details would be sharper in that part of the picture and colors and values (degrees of lightness and darkness) more intense. The midground would be in softer focus and lighter than the foreground. The background would be still lighter and less well-defined. This is the most natural approach.

|

| A simple landscape to experiment with |

|

| Annake toning a canvas |

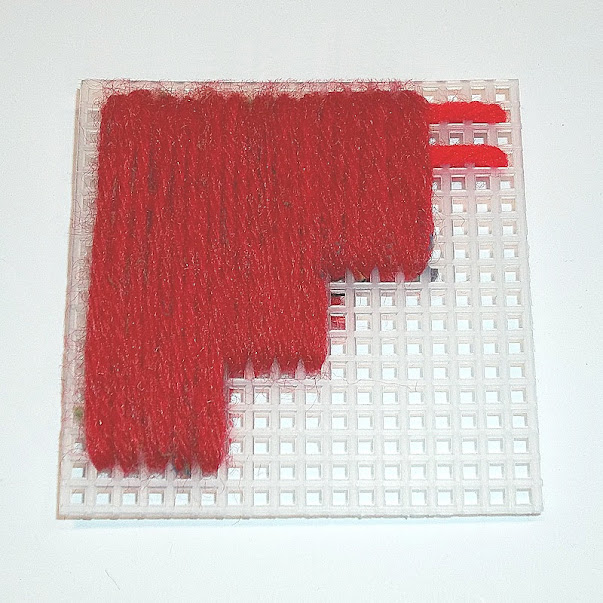

Try working on a colored background. You can tone canvas with diluted acrylic paint. That’s what I am doing in this picture. I often pick up unused canvases at yard sales. If there is a printed design on the canvas, I paint over it until it does not show through. You will not want to leave an area of bare canvas, so match your yarn or floss as closely to the background color as seems necessary. If you are working on fabric, try to find a medium tone of your major color. For example, use a medium blue fabric for a picture that is mostly sky, a medium green for a woodland scene, etc. You may want to limit yourself to other tones of the same color, plus black, white, and gray. Let some fabric show through. If you like this effect, you can apply it to other genres, like still lifes and even portraits. (For more about toning a canvas, see the post for June 15, 2014.)

Here are some generalizations about color that you may find useful.

- Color and value are not the same. Think of value in terms of intensity and saturation.

- A pure color, like the twelve seen on a conventional color wheel, is a hue. Every hue can be a tint (hue mixed with white), a tone (hue mixed with gray), or a shade (hue mixed with black). Use these variations to make your composition more interesting and realistic.

- Warm colors (red through yellow-green on the color wheel) seem to advance toward the viewer. Cool colors (blue-green through red-violet) seem to recede.

- Your picture should be predominantly warm or cool, depending upon the light, to assure color harmony. Warm colors are generally cheerful; cool colors are serene.

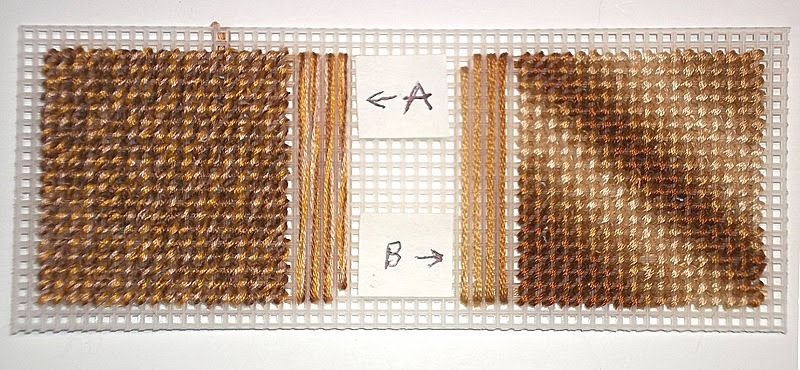

- A color may look very different in different contexts, depending on the colors that are next to it. Note how the colors seem to change in this needlepoint when the center squares change from white to black.

- The farther away an object is a picture, the paler (less intense, less saturated) it appears. Colors tend to gray as they approach the horizon.

- Grays are not always made from mixing black and white. Blending complementary colors can give you some interesting effects. Blue’s complement is orange. Brown is a part of the orange “family”. I have had some success in blending blues and browns in yarns and flosses. Not all combinations work. Blend a short length and place some stitches close together on a scrap of fabric. If you like the result, file the sample along with the color names or numbers that you used. Try to incorporate some of the complementary colors into your shadows.

|

| Needlepoint of colored squares |

Don’t get discouraged and quit if a project isn’t turning out the way you expected.

A few days ago, J. D. asked me how I was doing with a project. I told him I had come to love it and hate it with about equal intensity. Put the project away for a few days (no longer). When you look at it again, you may find there is nothing wrong with it. You may find you now know how to fix it. You may like it better than your original idea. Give it a chance.

Rules were made to be broken.

Take constructive criticism gracefully, but do not follow it until you have tried it and decided for yourself. Develop your own set of ideals. Listen to yourself. Be your own best critic.

Good luck,

This post by Annake's Garden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This post by Annake's Garden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.