This time we are going to begin with my version of an old bargello stitch pattern that produces the illusion that stitches pass over and under each other. The pattern, called Double Weave Stitch, is made with vertical and horizontal blocks of two contrasting colors. The original used 3-stitch blocks, but I thought 4-stitch blocks would be easier to see and understand. I have used #7 plastic canvas for easy visibility. I began in the first empty square in the upper left-hand corner with Color A (aquamarine here), but you could begin in the upper right-hand corner and work right-to-left instead of left-to-right. I brought my needle up through that space from the back and pulled the yarn through, making sure to hold the tail of the yarn against the back of the canvas and work over it to secure it. I skipped 5 threads (or bars of plastic canvas) downward and took the yarn to the back of the canvas. After making 4 parallel stitches this way, I had my first vertical block. I then made four more stitches in the top row, but each stitch covered only one thread. I repeated this pattern to the edge of my canvas. An empty horizontal block has been left bare in each of the top two rows in the illustration. The next row of vertical blocks are made below the four 1-thread stitches, with 3 horizontal threads left uncovered. Do at least two rows of the vertical blocks before you begin the horizontal blocks. The third row of vertical blocks repeats the first row, leaving out the 1-thread stitches.

To make the horizontal blocks, thread Color B (brown here) and secure it under stitches on the back of the canvas. Hold the last stitch of the first vertical block back with your thumbnail. Bring the Color B yarn up under that row and stitch forward horizontally across the bottoms of the 1-thread stitches, skipping over 5 threads and ending just underneath the first stitch of the next vertical block. Work 4 parallel stitches in this way and you have made the first horizontal block. The bottom stitch of each of these blocks covers the top of the stitches in the vertical block below it. This gives the illusion of weaving. You can work the color blocks alternately, or you can fill in all the vertical blocks your canvas will hold and then put in the horizontal ones. Do what is easiest for you. Wherever there is not enough room for a complete stitch or block, do as much of the stitch as you possibly can. When you do the same pattern on #10 canvas (see below), no canvas shows through and the illusion is complete. I recommend smoothing each block with the pad of your thumb as you complete it.

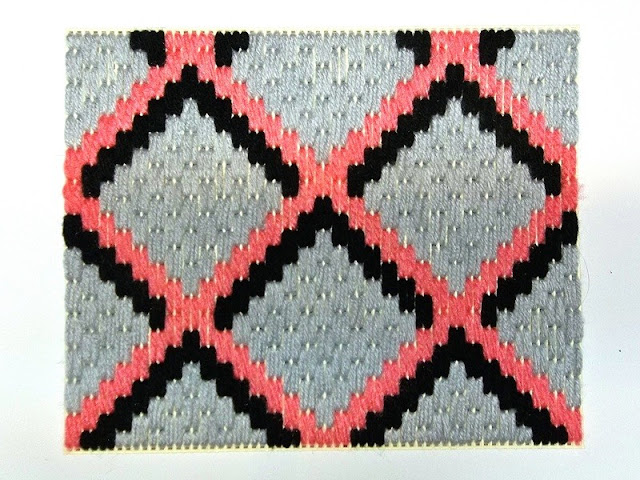

In our next project, we are doing a pattern of loosely interlaced “ribbons“, done here in 4 shades of red and 4 of blue. Because they are loosely spaced, some background shows through between the “ribbons”. I've indicated this background with white. Each stitch is doubled. Each stitch covers 4 threads. The stitches rise and fall diagonally by starting and ending 2 threads higher or lower each time.

|

| "Ribbons" sampler in 4 reds and 4 blues |

Use the enlarged picture at the bottom of this article as your guide. I began with the darkest red below the 16th thread at the left edge and worked 8 pairs of stitches upward and to the right. I then put in the 4 blocks of white stitches near the bottom and the top of the red diagonal. The spaces between the white blocks gave me the places to start the four shades of blue, which slant downward to the right. It also showed me the placement for the next sections of red “ribbon”. This is probably the most complicated pattern we have done yet, so take your time, study the picture, and be prepared to take out stitches if you make a mistake.

Is it possible to do the pattern with fewer colors? Certainly. This time I did the same pattern on #10 canvas with only 2 shades of red and 2 of blue. The pattern is tighter on the finer canvas and no canvas shows through. (You can do the ribbons in a single shade of each color, but it is not as interesting.) The red and blue yarns are twisted nylon novelty yarns. The white yarn is tapestry yarn, which is thinner and flatter than the novelty yarn, increasing the illusion that the white background is further below or behind the “ribbons”.

For those of you who like to include some tent stitches in your design, the background spaces give you an opportunity to do that. The top of the sample shows a background space done in the paired stitches over 5 threads. The bottom sample shows the background space done in continental stitch. You will need to make 3 stitches in each of the 2 top rows, 7 stitches in each of the 4 middle rows, and 3 stitches in each of the 2 bottom rows.

Patterns like these have many uses. They may be framed as examples of geometric or “op art” design. They make excellent pillow tops. In both cases, I suggest you key the color schemes to the décor of the room where they will be used — whether in your own home or as gifts for someone else. Other uses include desk sets, purses, tote bags, place-mats, and table runners. It is relatively easy to “translate” such designs to graph paper (using one square of graph paper for each square of canvas mesh), for larger projects, such as needlepoint or latch-hook rugs.

Remember that practice makes for perfect projects.