|

| "Incoming Storm," photo by J.J. |

Many trees change form drastically as they mature and age, sculpted by wind and weather. A dwarfed, twisted tree at timberline can give real drama to a mountain scene. Some trees define the seasons. Last autumn we were in the high country, photographing the glorious colors of aspens and scrub oaks against the darker evergreens.

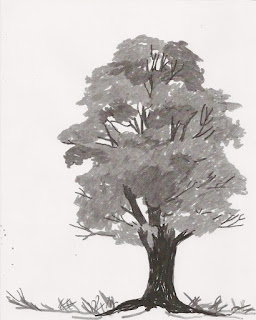

I like to study deciduous trees in the winter when their basic skeletal structure is most evident. Then I revisit the trees in the other seasons, sketching or photographing them to understand how that skeleton supports the masses of their leaves. Fruit trees are especially interesting because they have a flowering stage — often before any leaves have formed — and provide attractive backgrounds when the fruit is ripe. If I understand the way a tree is growing, I can anticipate where the masses of foliage are going to be once they develop.

|

| Ornamental fruit tree in bloom |

Trees are, of course, vital to many landscape compositions in graphic arts and needle arts, but they can compliment many other types of composition. For example, they can contribute in many ways to photography: to enhance an outdoor wedding or family picnic, as backgrounds for pictures of animals that use them for food and shelter, to soften the lines of street scenes or individual buildings, etc. One way to change a potential landscape or a picture with houses, for example, is to move the surrounding trees into different positions.

Here is a quick watercolor study of a palm tree that I made many years ago in Panama. Imagine that you can "borrow" my palm tree. What do you see beneath it? An abandoned beach ball? A picnic lunch? A sunbather stretched out on a blanket? An animal digging in the sand for turtle eggs? See how a single tree can stimulate your imagination? Download the tree. Make a sketch of what you would include or look for a photograph that you could adapt.

Here are some things to consider when looking at trees. Study the patterns created by the direction of the light. If the sun shines directly on the tree from the front, which parts of the tree are darkest and lightest? What sorts of patterns are created around the tree? Where do the shadows fall? How do these things change when the trees are lit by light coming from behind them? (Sometimes it helps to half-close your eyes to really distinguish the masses of dark and light.) If you are sketching the tree, put in the masses of middle value first. Then concentrate on the lighter and darker masses. Trees do not grow out of the ground like fence posts. Include the roots and the spread of the tree toward the roots in your study (sketch) of the tree. If you are doing a picture that includes a group of trees, remember that distance tends to add gray to more distant objects and try to make the farthest trees less distinct than those in the foreground.

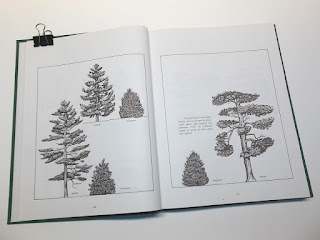

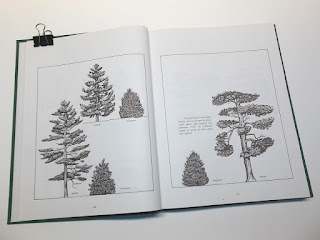

I have, as a prized possession, a book written in 1983 specifically for landscape architects and nurserymen. It shows detailed drawings of trees and shrubs commonly used for those purposes. The pictures are all drawn to the same scale, so that you can make combined groupings and be sure that they would look natural together (in a park or garden, for example). It is also possible to enlarge a tree — or even part of a tree — to show how it would look beside or behind a building. You can also enlarge foreground trees and reduce background ones to show realistic perspective. Remember that distance not only makes trees look smaller. It also makes them look paler.

|

| One of Annake's transparencies |

Finally, the trees can be copied on clear overlays, and be superimposed one on another. Although my book is probably long out of print, comparable photographs or drawings can be found in library books or online. Look for such topics as Forestry, Trees of <insert your country, region, continent, or the World>, Landscaping, or Ornamental Trees.

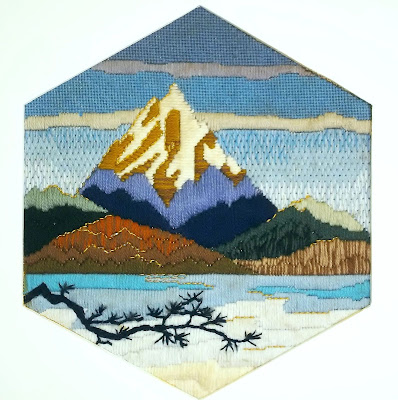

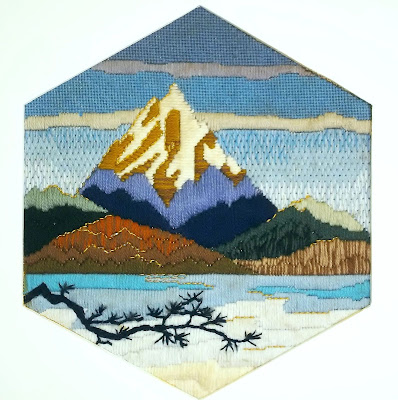

Here is a simple way to determine whether a tree might enhance your picture. When you have your photograph or sketch well organized, place a clear plastic overlay of the tree shape you are considering on top of it. This doesn’t have to be a detailed picture of the tree, just its general shape and growth pattern. You would be surprised, for example, how many shapes different kinds of evergreens can take. I have built up a collection of such overlays that I keep in a file folder. Because they are transparent, I can move them into any position I want on top of my sketch, reverse them, show only a portion of the tree, etc. Move a tree that blocks the view of a building to behind the building. You will still have its shape as a point of interest in the composition, but it will no longer overshadow the building or hide interesting architectural features. Even a single branch can have a big impact as you can see in this needlepoint picture.

|

| "Cascades," needlepoint by Annake |

|

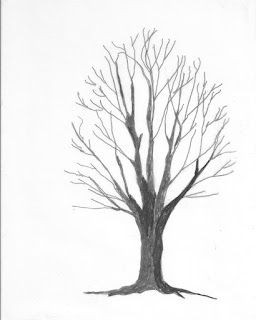

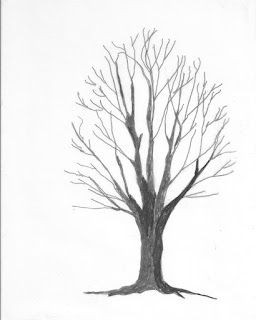

| Trunk and limbs |

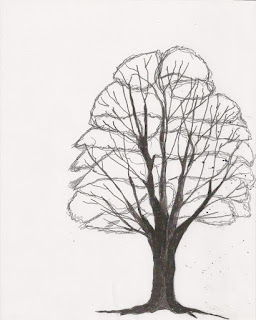

Let's go step-by-step through a tree sketch. I am going to use a simple #2 pencil because it is the one you are most likely to have available. I recommend you do this exercise in late spring or summer, when trees are usually in their best condition. It is neither necessary nor desirable to draw, paint, or embroider the majority of tree branches. Get the larger ones and enough of smaller ones to show the directions in which the tree is growing. I like to think of the limbs as

gesturing in these directions. After all, when you portray a tree you are making an image of a living, growing creature, constantly adapting to its environment. Its growth is dictated by the amount of sunlight it gets and the directions and angles of that light. It responds to the winds and the amount and kind of moisture it gets — rain, fog, snow, etc. Its form may be changed at various stages of its life by the presence of obstacles like large rocks, fences, buildings and other trees. Try to see these influences in the living tree and indicate them in your sketch. And don't forget to show some roots in your sketch to connect the tree with the ground. When I am satisfied with my sketch, I move on to the next step.

|

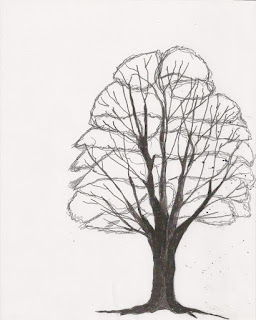

| Foliage blocked in |

Just as it is not necessary to show all the tree limbs, it is not necessary to show all the foliage. If you look at a single tree, you will see the foliage is arranged in large clusters with parts of the trunk and limbs showing through between them. Look at the clusters. Which ones seem to be pointing — or gesturing — toward you? Which ones are pointing away from you, out to the sides, or up at the sky? Treat them like separate pieces in a jig-saw puzzle. Sketch the general shapes of the most important ones. You don't need all of the clusters to make the tree look real. Make some little irregularities in the outlines of the shapes for realism. Indicate the larger limbs and parts of the trunk that show between the masses of leaves and where they may be seen in "holes" in the foliage. Carefully erase any of the trunk or limbs that you don't want to have showing in the finished design. (Pencil erasers tend to smudge, so it is a good idea to have a piece of sandpaper to remove the surface of the eraser as it starts to darken. A kneadable eraser is a good thing to have.)

|

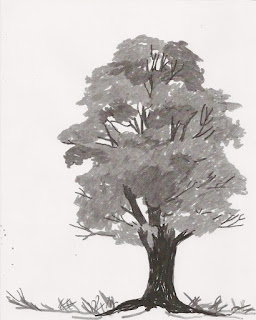

| Values |

Now it is time to consider the

values of the masses of foliage. Value refers to the relative lightness or darkness of objects or areas. (We are not going to consider color at this stage.) Which cluster is the lightest and brightest in the tree? Leave it nearly as white as your drawing paper. Check to see if there are any areas that are almost as bright. Fill them in as lightly as possible with your pencil. Now find the darkest cluster. Consider it carefully. Is it darker than the tree trunk and limbs? About the same? Lighter? Fill it in very solidly, pressing hard with the tip and side of your pencil point. Go over it as many times as you need to give it the value you want. Continue working alternately with the next lightest and next darkest clusters until all of them have a value. Check the whole composition against the real tree for accuracy. Do you need to further darken any limbs or parts of the tree's trunk?

If you have easy access to the tree, this may be a good place to stop sketching and leave color decisions to another day. Put your sketch away and don't overwork it. If you can get a couple of photographs of the tree, that is an excellent idea. It might rain tomorrow.

|

| Summer colors or autumn? |

|

| Evergreens |

So far we have only discussed broad-leaved trees. Evergreens present different problems and possibilities. Because so many conifers have a generalized triangular shape, many people never try to learn the differences between the species and assign them cookie-cutter appearances. We have a number of different species close by. I love to look at them just before sunrise. They do start out as very simple silhouettes, but, as the light begins to filter through them, you see that they grow in very different ways. Some of them reach for the sky with tiers of V-shaped branches. Others are less dense and produce their branches at much wider angles with their trunks. Still others have branches that curve or angle downward, sometimes touching the ground. And there are ground-hugging evergreens which don't take a tree form at all. They are all worth study and are particularly beautiful in winter.

|

| Pine cones, photo by J.J. |

Trees that lose their leaves in autumn are known as broad-leafed trees. Evergreens have needles or scales instead of leaves. They lose these gradually all year long. You can usually find a pile of them underneath the tree. A number of evergreen trees bear cones and are classified as conifers. A photograph or sketch simply featuring cones and needles can be very decorative. If you are not familiar with the evergreen trees in your locality, consult a tree guide book or have a talk with someone from a local nursery.

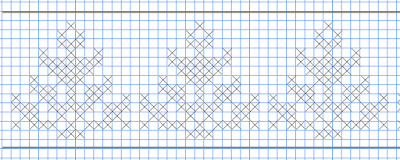

I often use trees to design needlework projects. Some of them are highly stylized like the evergreens and aspens in the two end photos, while others are more naturalistic like the design in the center.

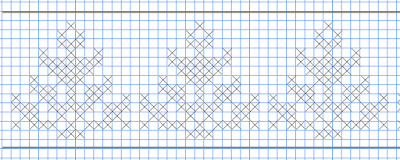

Simple tree silhouettes, particularly of evergreens, make nice border designs for illustrations, needlework borders or all-over patterns, photo mats, etc.

|

| Chart for cross-stitched border of evergreen silhouettes |

It is often useful to study how artists have represented trees in their works. For a long time trees were simply backdrops and not done with particular attention to detail. It wasn't until about the middle of the 19th Century that, particularly in France, they became viewed as subjects worthy of painting for their own sake. Jean Baptiste Camille Corot led the field in this respect. He strongly influenced the Impressionist painters. They, in turn, influenced whole schools of contemporary and Post-Impressionist artists. Pointillist painter Paul Signac also did beautiful trees. Look at paintings by your favorite painters to see how they handled the subject of trees.

If you missed our recent Arbor Day post, follow

this link. For more information about trees, check our Extras section for "Teachable Moments" activities and a Self-Teaching Unit for teens. And, if you can, plant a tree!

Now, as our favorite tree-house builder loves to say: "To the trees!"

This post by Annake's Garden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This post by Annake's Garden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.