Hello, again, and Happy New Year! It’s taken a while to get back up to speed after the holiday break, but we’re brimming with ideas for a new season of posts. We will introduce you to some new artisans, new arts, and new techniques for some crafts we’ve explored in previous articles. We will take up new needlework topics like trapunto and reverse applique and non-needle arts like batik; but that doesn't mean we will neglect old favorites like needlepoint: we plan to feature new ideas for shaped four-ways, patterns based on optical illusions, and a hybrid form of tapestry work that I like to call “stained-glass stitchery.” We hope each of you will find something you like and want to try. As for needlework, we plan to devote quite a bit of space to folk embroidery, starting with this post.

What Is Folk Embroidery?

|

| Hand-made bone needle, used to sew the tunic shown below |

Folk embroidery, like most folk arts, began in rural areas, where people made simple homespun fabrics or in remote places where the skins and furs of animals were used for clothing, bedding, and even shelter. Decorative stitching and applied objects served to make coarse, drab fabrics appealing and to express individual creativity. At various times and places, stitches were combined with feathers, seeds, bones, teeth, claws and porcupine quills. The first “sequins” were probably fish scales or beetle wings. Sinews and plant fibers were used before thread, floss or yarn were invented. Did you know that the first known needles were carved from ivory in what is now France some 20,000 years ago?

|

| Viking style tunic with fishbone stitch seams |

J.D. and I occasionally do programs about life in the Viking Age. Because we have to make or trade for all of our garb, tools, and gear, we do a great deal of research to assure what we use and show is as authentic as possible. Unfortunately fabric, thread, and yarn are fragile compared to stone, metal, and wood. They rarely survive for centuries. For embroidery, I study photographs of very old pieces from museum collections to identify familiar stitches and to understand how unfamiliar ones were made. I compare pieces from different geographic areas. It is like a treasure hunt. Often it is possible to follow the progress of a pattern or technique over great distances. For example, one can see how the wool and silk embroideries brought by the Moors when they conquered Spain became the inspiration for the exquisite blackwork embroidery of the Elizabethan Age in England. Or one can follow techniques from the Byzantine Empire up the great rivers to the Baltic states, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia.

I was offended some years ago when a so-called “expert” on the Viking Age (a man, of course) proclaimed that the women of that time knew only eight embroidery stitches. How do I know that he was wrong? First, five decades of teaching have shown me that most innovations are the result of mistakes – such as not having enough of one color of thread to do what you’ve planned; or of misunderstandings – the fishbone stitch that seams the tunic above can be accomplished two entirely different ways, and it’s impossible to tell which is used unless you can see the back of the stitch; or of desperation – fabric was precious in those days, and women had to salvage what they could when Ole got too fat for his britches, or got blood on his new tunic butchering a pig (or a Saxon, as the case may be). And what do women do when they get together? They exchange information on everything from recipes and child care to networking and politics. They always have; they always will. Don't you think they would have done the same thing with embroidery stitches and patterns?

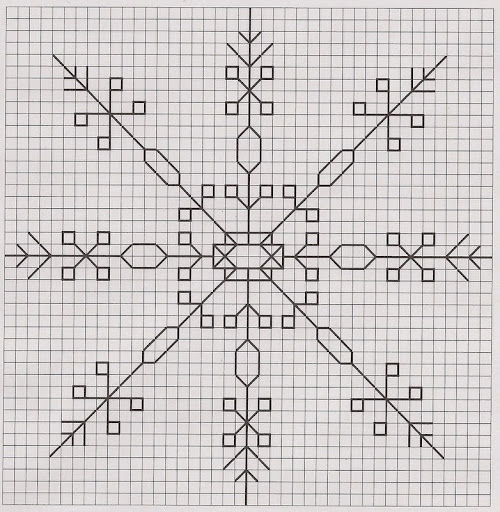

Let me show you how you can learn eight stitches in a very short time. You will need a scrap of fabric, a needle, and three colors of floss. Start with the simplest possible stitch –- the running or basting stitch (see below). Make ten rows of this stitch evenly spaced apart. (I have made very large stitches for visibility; yours don't need to be so large. The stitches will look neater at a smaller scale.) Be sure each row is firmly anchored at both ends.

Leave the first row of stitches as it is. With the second color, and working from the opposite direction, fill in the spaces between the stitches in the second row. This is the

double running stitch and is the basis for the

Holbein stitch I wrote about last summer. In the third row, the running stitches are

whipped (overcast) with the second color. This is the whipped running stitch. The second color stays on top of the fabric except at the two ends. Make the fourth row into a double running stitch like the second row. Then

whip (overcast) all the stitches with your third color, which stays on the surface except at the ends where it pierces the fabric. This is the

whipped double running stitch.

The fifth row illustrates the laced running stitch, in which the second color stays on the surface and is pulled into a little arch under each stitch –- with a longer, shallower arch in the opposite direction between stitches. This gives it a pretty scalloped appearance. (If I were using this on linens or a garment that had to be washed, I would use a strand of the background thread to couch down [hold the stitch in place with a tiny upright stitch] each arch at its center.) Make the sixth row into double running stitch with the second color. Then lace it with the third color. This is the laced double running stitch. Because the arches are caught at the joining of two stitches rather than crossing an empty space between stitches, the top and bottom arches are the same size and the scalloped effect is lost. This is another stitch that benefits from couching. Make the seventh row into double running stitch, but this time use only your first color. Keeping the second color on the surface except at the ends of the row, loops the floss around each place where the running stitches join. This is the Pekinese stitch, which doesn't usually require couching. (If you know how to back-stitch, you can whip, lace, and do Pekinese stitches on a row of back-stitching just as you did on the running stitches – and thereby double the number of stitches I promised to show you!)

The last two stitches are worked between two rows of the running stitch. For the first of these, make a cross-stitch in each space between the rows of running stitches. This has no name as far as I know. The shapes created, however, are often called lozenges, so I suppose we could call it the lozenge stitch. The eighth stitch requires an extra step. First, turn both rows into double running stitches with your first color. Bring your needle with the second color up halfway between the two rows of stitches. Make a Pekinese stitch around the first joining on the bottom row of stitches. Then make a Pekinese stitch on the joining directly above on the top row. Continue alternating bottom and top stitches all the way across, ending by pushing your needle down midway between the rows at the other end. This is called the interlaced double running stitch.

Now you know eight more stitches, based on nothing more than simple running stitches and the concept of wrapping another thread around or between them. Wasn't that easy? Keep experimenting with doubling stitches, reversing them, combining them or adding more colors. Who knows? Maybe you will invent an entirely new stitch! You can see some new stitches on the hand-embroidered blouse below.

Enjoy your new stitches,

|

| Hand-embroidered blouse from Hungary |

This post by Annake's Garden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This post by Annake's Garden is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.